Foreword

A lot of the new entrants into the business of motion picture production in Nigeria think that the business of filmmaking started with Nollywood. It did not. Nigeria had an indigenous film industry that dates back to the 70’s. Then, filmmakers such as Dr. Ola Balogun, Late Chief Adeyemi Afolayan, late Chief Hubert Adedeji Ogunde, and Chief Eddie Ugbomah amongst many others made films on celluloid either on 35mm colour or 16mm colour. But while the exploits of most of these pioneer filmmakers may have been fairly documented in some of the early books written on the film industry in Nigeria, notably Francoise Balogun’s The Cinema in Nigeria and Professor Hyginus Ekwuazi’s Film in Nigeria, there have been very little mention about a period in the history of the Nigerian film industry where making films using the reversal technology reigned. That was the period of the 80’s when filmmakers such as the late Yemi Meshioye led the crew at Meshfilms Limited to pioneer the unconventional shooting of feature films with reversal film stocks as opposed to negative film stocks which was standard for making films at the time.

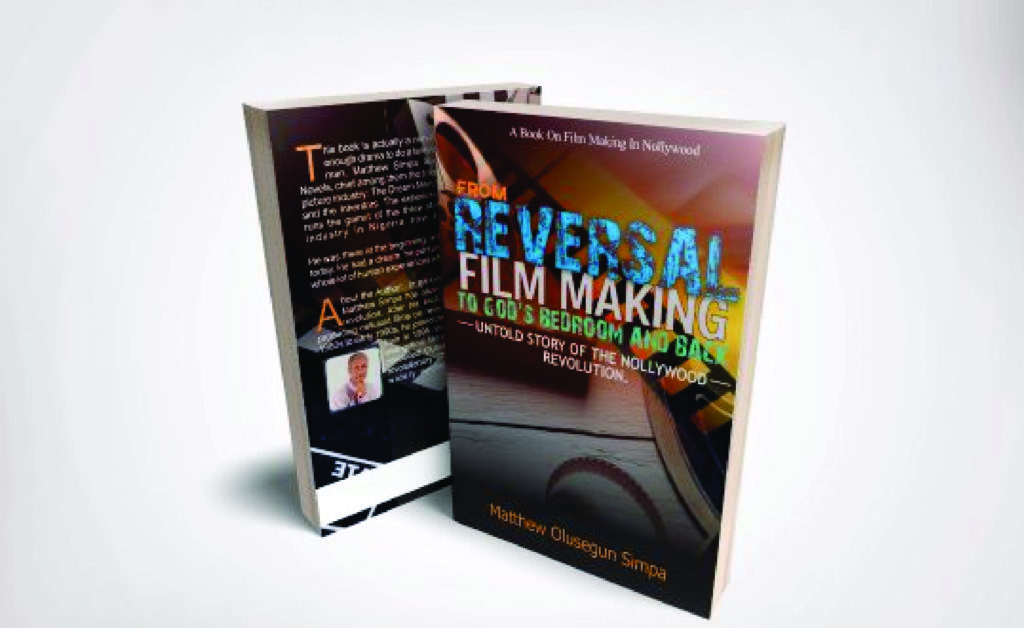

It is a part of the untold story of that period in the evolution of the film industry that is told in From Reversal Filmmaking To God’s Bedroom and Back… Untold Story of the Nollywood Revolution, the bookby the accomplished filmmaker Matthew Simpa who was a member of the Meshfilms family and a key figure in the production of some of the film projects by Meshfilms. Those films including Lori-Ere, Ijagbemi, Gbegede Gbina and Iji Aye unarguably became pathfinders for filmmaking in Nigeria.

I am familiar with most of the books that have been written and published on the Nigerian film industry. This book by Simpa is probably the second book on the Nigerian film industry of the 70’s and 80’s devoted to the career journey of a versatile thoroughbred professional with ramified experience and multi-faceted professional training. The first of this kind of work that I have read is the book by the late legendary filmmaker Eddie Ugbomah titled Eddie Ugbomah. But unlike the book by Chief Ugbomah, which is an autobiographical account, Simpa saves the full account of his life for another publication and shares just the story of his career journey pre-Meshfilms, his personal recollection of how they made ‘magic’ with films like Iji Aye at Meshfilms and then his journey post-Meshfilms in this book. The result is a very personal story of those moments that shaped his dream, about the field experiences that sharpened those dreams and about the struggle to fulfill them. It is the story of a hardworking, humble and an honest personality who should be righty acknowledged for his invaluable contribution to the evolution of the Nigerian visual media industry that is today a global household name.

The contributions of this book are manifold. But two things particularly stand out for me. First is that through an account of his career, the author offers a very resourceful and highly engaging book that lends tremendous insight to the creative exploits of Meshfilms and that of other filmmakers of the era of reversal films. Secondly, each chapter of the book is lucidly presented to justify the competence and professional experience of the author in filmmaking.

Although there are still so many efforts to be recorded regarding this period of Nigerian cinema (and the author makes no pretence about writing a definitive book on that period and history of Nigerian film industry), we must commend Simpa for taking this bold step in documenting a significant aspect of the story, which I consider central to our understanding and appreciation of the history of the Nigerian film industry. Although usually a labourious task, but am sure Simpa considers it an honour and a great responsibility to add to the growing body of works that are helping to define the emerging trends with the vibrant Nigerian film industry.

I can imagine that Simpa’s saddening thought and our own thoughts too will be that nearly all the reversal films and even the films that were produced on bigger gauges may not have been preserved for posterity, I think we should be consoled by the fact that one of the key players of that period has at least captured and told a compelling story of the essence of that period in our filmmaking history.

I believe that this book is a valuable contribution to the field. The ultimate value of the book for me is that it points us both backwards to the past and forward to our future. I recommend it to everyone who is interested in the history of the Nigerian reversal film tradition especially and in the history of the Nigerian film industry before Nollywood. It is a welcome addition to the growing body of works on the Nigerian cinema and I feel honoured to be able to greet this new book in its opening pages.

Shaibu Husseini, PhD

Senior Teaching/Research Fellow

Department of Mass Communication

University of Lagos

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Matthew Simpa was born in, Agege, in 1964. He began his film making career with Meshfilms as an Assistant Film Director in 1986. This was two years after graduating with a cinematography certificate from Nigerian College of Film, Owo, Ondo State. He was actively involved in the innovative film making process of using reversal film stocks to shoot theatrical films. He was also part of a series of hit Yoruba home movies in the early 1990s. In 1995, he veered into evangelical film making. Between 1995 and 2000, he directed over twenty movies on video among which was Valle de Baca, the first successful home movie shot in Benin Republic. Since 2004, he has been involved mostly in Christian television programming. He has also directed two soap operas, one in English (The Burning Spear) and the other (Angeli Nigeria) in Yoruba.

In recent times he has worked at Galaxy Television and is presently the General Manager of Ben Auto/Stedik Resources Entertainment Ltd in Lagos. His two most recent movies are Outside the Box (2014) and yet to be released Yoruba film titled Ito Okurin which he produced.